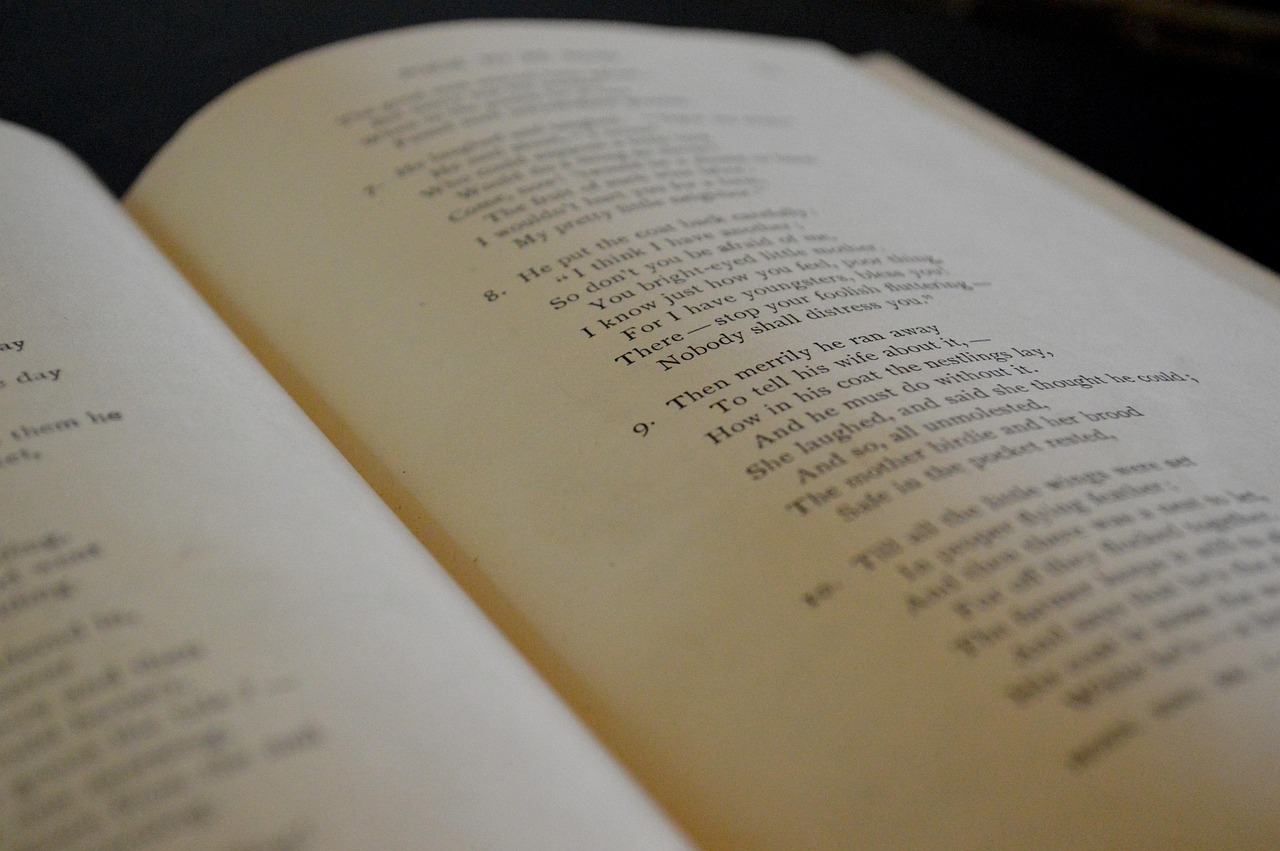

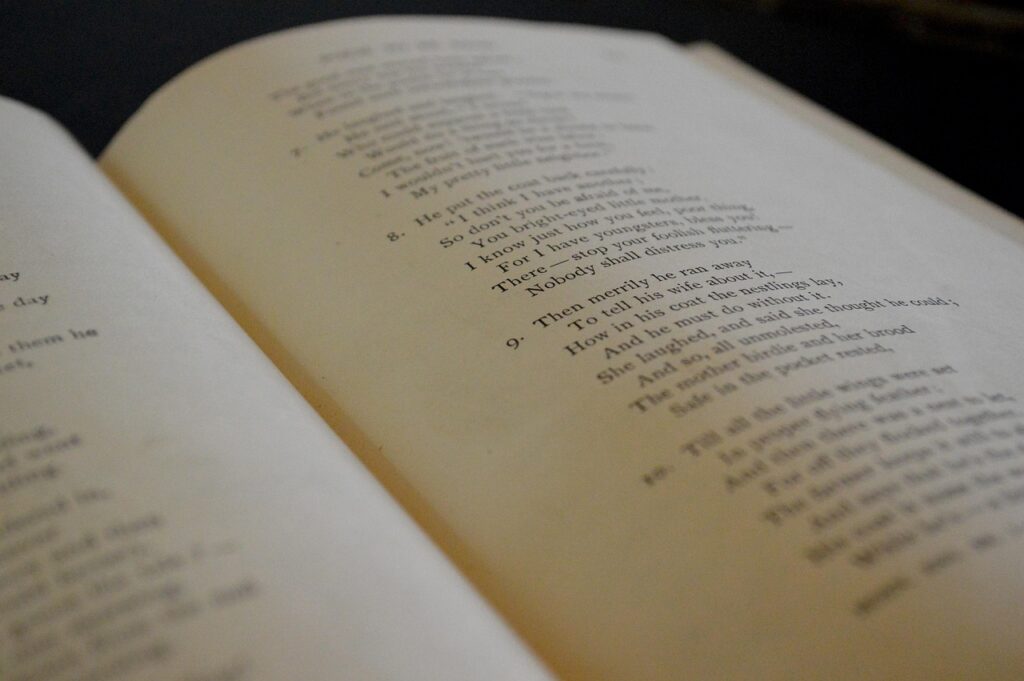

A poem holds a structure that is visible to its audience. And when the lines are read aloud, the words should sit well together–one after another–creating a pleasant sound. This sound appeals to the reader in a different way than prose does. Even though some poets vary their creation of poetry and have adopted different structural and sound techniques, it should be pretty obvious that you’re looking at a poem and not something else. Here’s a few basic elements that you would find in poetry to help you determine what makes a poem a poem.

Image by Chris Pastrick from Pixabay

Structure

Prose and poetry should be easy to differentiate from each other. Prose is longer writing and includes the type you are reading now. You would also find it in magazines, newspapers, books, pamphlets, etc. It’s ordinary, every day writing that doesn’t rhyme or have a rhythm. A poem, on the other hand, has a distinct look that’s usually easy to spot. The lines are shorter and are often broken up into phrases. It might also employ lines breaks and white space unlike prose would, which would be confusing to the reader. In a poem, words are placed purposefully and to create appealing sounds.

Lines and stanzas

Poems are written in lines first and foremost. These lines do not always equal complete sentences. When referring to something specific in a poem, we use the line number. Even if there’s only one word on a line, it counts.

Sometimes a poet divides these lines into stanzas, which are like paragraphs for poetry. When a stanza is created, it’s because the lines within it are related in some way. That relationship could be based on many things. Some examples include a theme, a metaphor, an event, or a description. Stanzas help the reader to better digest the contents of a poem. It can be easier to follow the poet’s meaning one stanza at a time and then put your findings together at the end for an overall interpretation.

Rhythm

Poetry also has rhythm–a sound or beat that runs throughout it. You should be able to hear it when the poem is read aloud. It’s similar to a rhythm you might hear in a song–a recurring pattern or tempo that you grow to expect. Rhythm in poetry, as in music, creates ease for the reader. Meter most often creates this rhythm, but a poem can have rhythm and not have meter or rhyme.

Connection

Poems take the ordinary and connect it to something palatable, but also unexpected. A poet may be describing how he or she feels about looking out the window one January morning in Texas and seeing snow on the ground. Because this occurrence is rare where the writer lives, they may come up with a way to express how rare it actually is. They might use a metaphor, simile, or personification to give the reader an image that represents it. Doing so creates a connection in the reader’s mind between what is being described in the poem with something seemingly unrelated but that drives the point home.

Inspiration

If you’re just beginning to read poetry and thinking about writing it, start first by understanding these three parts of a poem. It will have a structure that indicates it’s a poem and not prose. It will produce an almost melodic sound because of how each word is placed side by side. And the poem will in some way paint a picture in your mind–whether that’s through vivid language or through the use of comparisons. Take a look at a few of the poems I’ve linked below to see some examples of these elements.

- “Eagle Poem” by Joy Harjo

- “Oranges” by Gary Soto

- “The Bean Eaters” by Gwendolyn Brooks

- “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou

- “After Apple Picking” by Robert Frost

If you’re inspired, and you’d like to write your own poems, I have a new digital course I’ve launched that will help you get your ideas down quickly and turn those ideas into a completed poem.